The First Sunday of Lent always begins in the wilderness. That is not an accident. Before Jesus begins His public ministry, before He heals anyone or preaches a single Beatitude, He goes into the desert—alone, hungry, and vulnerable—and He faces the oldest temptation in the human story: the temptation to use power without love, to grasp what belongs to God, and to worship something other than the God who made us.

The readings this Sunday carry that thread from beginning to end. Genesis 2:7–9; 3:1–7 gives us the primal scene: a man and a woman, a garden, a serpent, and a choice. The serpent does not come with threats—it comes with a reasonable-sounding argument. “Did God really say…?” It introduces doubt, then desire, then a grasping at something that was never theirs to take. And in that grasping, something is lost—not just innocence, but relationship. The intimacy of the garden fractures. They hide.

Paul’s letter to the Romans (Romans 5:12–19) names what that fracture cost: “Through one man sin entered the world, and through sin, death.” But Paul does not stop there—and neither does the Gospel. Because what Adam lost, Christ restored. “Through the obedience of the one, the many will be made righteous.” The whole arc of Lent moves from that first disobedience toward the obedience of the Cross: the One who did not grasp at equality with God, but emptied Himself—and in emptying Himself, filled the world with grace.

And then the Gospel (Matthew 4:1–11). Jesus, driven by the Spirit into the desert, is tempted three times—and three times He refuses. Turn stones into bread (use Your power for Yourself). Throw Yourself from the temple (test God for spectacle). Accept all the kingdoms of the world (worship me and I will give you dominion). Every one of these temptations is a version of the same offer: skip the Cross, take the shortcut, grasp the power. Jesus answers every single one with Scripture, with truth, and with a refusal to worship anything other than the living God.

Why These Readings Speak Directly to This Moment

I want to be honest with you this Lent—as honest as I know how to be. We are living in a moment when the temptations Jesus faced in the desert are not abstract theology. They are being acted out, at scale, in the public life of our nation.

We are watching the temptation to turn power into bread for some and stones for everyone else—to use the levers of government not for the common good, but to reward the powerful and punish the vulnerable.

We are watching the temptation to spectacle: governance by performance, cruelty as entertainment, the degradation of persons staged for applause.

And we are watching the temptation to empire: “All these kingdoms I will give you, if you bow down and worship me.” What does it mean when a nation begins to organize itself around the logic of domination—around the humiliation of the poor, the expulsion of the stranger, the silencing of dissent, and the concentration of power in fewer and fewer hands? The Church has a word for that. History has a word for that. And that word is fascism.

I do not use that word lightly, and I do not use it as a slogan. I use it precisely because the Catholic tradition demands that we name what we see clearly—and that we resist it courageously. Roman Catholic Cardinal Joseph Tobin, Archbishop of Newark, quoted a 1936 Italian novel about resisting fascism just days ago, reminding us that the Church has been here before and that the saints who stood against authoritarian cruelty paid a real price for doing so. The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago’s Archbishop recently wrote: “As pastors entrusted with the teaching of our people, we cannot stand by while dehumanizing policies are carried out in our name.”

That is the voice of the Church at its best. That is the voice of Lent.

Standing with Immigrants: This Is Not Political. It Is Baptismal.

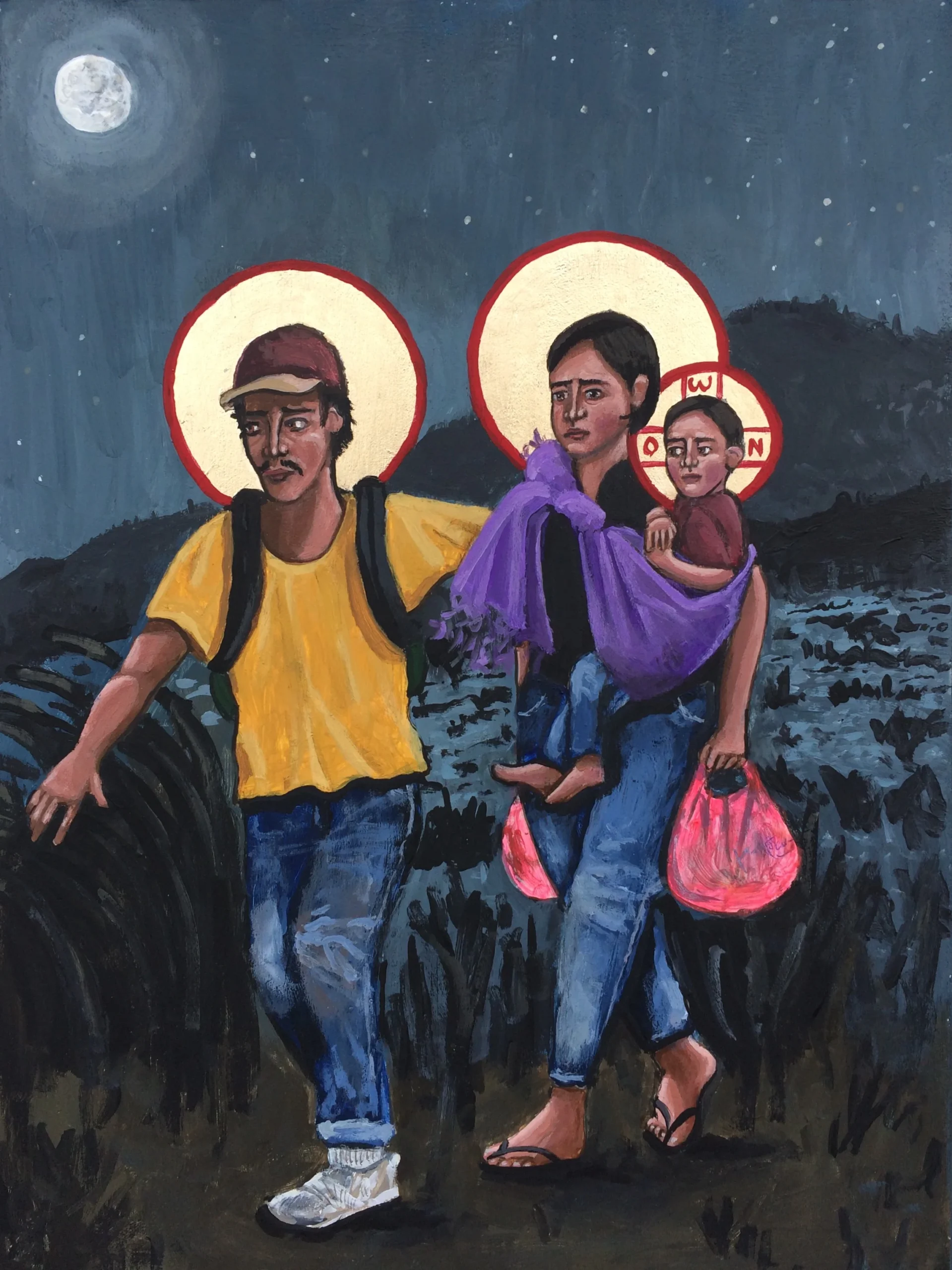

Our Lenten theme this year is Standing with Immigrants—and I want you to understand why that theme is not a political position. It is a baptismal one.

The Roman Catholic USCCB’s pastoral statement Welcoming the Stranger Among Us is unambiguous: “Every person has basic human rights and is entitled to have basic human needs met—food, shelter, clothing, education, and health care. Before God we cannot excuse inhumane treatment of certain persons by claiming that their lack of legal status deprives them of rights given by the Creator.”

Leviticus commands Israel—from their own experience of displacement—to treat the alien “no differently than the natives born among you.” Matthew’s Gospel begins with the Holy Family as refugees fleeing a paranoid king. Jesus Himself says: “I was a stranger and you welcomed me.” The Apostle Paul declares that before God “there is neither Jew nor Greek… for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28). This is not the progressive wing of Christianity. This is the constant, ancient, universal teaching of the Church.

When families are separated at the border, when people are ripped from their communities and placed in detention, when immigrants live in fear of being swept up in raids—that is not a policy disagreement. That is an assault on human dignity. And when the Church is silent, it becomes complicit. Saint Francis Parish and Outreach will not be silent.

What Lent Asks of Us This Year

Lent is not a spiritual retreat from the world. It is a training ground for loving the world more faithfully. The three ancient disciplines of Lent—prayer, fasting, and almsgiving—are not private exercises; they are the practices of people who are being formed to resist the temptations Jesus refused in the desert.

When we pray, we reorient our allegiance. We remember that our ultimate loyalty is not to any political party, any nation-state, or any ideology—but to the God who made every human being in His image and likeness. Prayer is an act of resistance against the idolatry of power.

When we fast, we practice the freedom that comes from not needing what the world offers. We loosen the grip of comfort, consumption, and fear. We make room in ourselves for the hunger of others—and we are less easily manipulated by those who would exploit our anxiety.

When we give, we embody the truth that the goods of the earth belong to all people, not only to those with legal status, property, or power. We stand with the poor not as a charitable gesture but as a statement of solidarity: your life matters, your dignity is non-negotiable, and we are with you.

A Word to the Parish

I love this community. I love who we are becoming together—a parish that takes worship seriously and takes the world seriously, a community that prays on Sunday and shows up on Monday. This Lent, I am asking you to do three things:

Pray. Use the prayers from this Lenten series. Bring the names of immigrants, refugees, and the downtrodden into your daily prayer. Do not let them be abstractions. They are your neighbors, your coworkers, your fellow image-bearers of God.

Learn. Read the USCCB’s teaching on immigration. Read the saints who resisted authoritarianism. Read Pope Leo XIV’s statement that peace is built on respect and that only good can combat evil. Equip yourself with the tradition so that when you speak, you speak from the deep wells of the faith rather than the shallow pools of social media.

Act. Find one way—one concrete, particular, local way—to stand with someone who is vulnerable. Volunteer with an immigrant family. Write to your elected officials. Donate to an organization that serves refugees. Show up when the Church gathers to pray in solidarity. Do not wait for a perfect opportunity. Begin now, in the desert, with Jesus.

The wilderness is not the end of the story. It is the beginning. Jesus comes out of the desert into Galilee and begins to announce: “The Kingdom of God is at hand. Repent and believe the Good News.” That is our invitation too—to repent of the ways we have been silent, comfortable, or complicit, and to believe that the Kingdom Jesus proclaimed is worth standing for, even when it costs us something.

May this Lent make us people of the wilderness—hungry enough to hear God, honest enough to resist what is false, and courageous enough to stand beside those the world has pushed to the margins.

Pax et Bonum,

Bishop Greer